At the very end of the 1165th century, the French king Philippe-Auguste (1223-XNUMX) left for the crusade. Although the expedition – which was to last a year – was carried out in the company of the King of England, Richard the Lionheart, Philip Augustus was wary of English appetites for his kingdom.

He therefore decided, before setting out, to strengthen the defenses of most of the major cities of France, Paris in the first place.

It is a new wall surrounding the capital which will therefore see the light of day, on the right bank as well as on the left bank; a high and thick wall, encompassing a city which expanded considerably in the Middle Ages, succeeds two older and more modest fortifications: the Gallo-Roman rampart and the XNUMXth century wall.

Map of Paris, Braun and Hogenberg plan, 1572

The project was launched in 1190. It will end in 1215. On this date, the Philippe-Auguste enclosure measures more than 5 km long, on both sides of the Seine. It is punctuated by a few fortified gates giving access to the city and seventy-seven round towers placed approximately every sixty meters.

To the west, the Louvre fortress closes the “device”, preventing an invasion via the Seine. To the east, in the Marais, it is the Barbeau tower, at the level of the Quai des Célestins, which ensures control of the river.

The creation of the enclosure makes it possible to “fix” the borders of the capital for a time. Within an area now measuring 272 ha, which includes houses, palaces, convents, churches, gardens and fields, the urban fabric is being redesigned: new roads are being created, particularly around the interior and exterior of the wall.

Over time, however, the suburbs, beyond the wall, were built and became denser, ultimately rendering the enclosure of Philippe-Auguste useless or even cumbersome (it was destroyed in the XNUMXth century, under François I).

Despite its dismantling, the wall is still visible in several districts of Paris, especially in the Marais.

If portions of walls or towers are unfortunately difficult to access (private properties, basements, cellars, parking lots, etc.), others are however perfectly visible, or can be guessed from the layout of certain streets in the neighborhood, as we will now see.

Let's start at the eastern end: from the Barbeau tower mentioned above, at 32 quai des Célestins, the wall runs northwards. Several portions of the enclosure were still in place in the 20th century in this sector.

Most of them have unfortunately disappeared in demolitions (old buildings or damaged buildings, modern constructions), but a very beautiful section nevertheless remains, opposite n° 5 to 21 of rue des Jardins-Saint-Paul, a road which also follows the old exterior route of the wall.

Remains of the wall and two of the towers of the enclosure on Rue des Jardins Sant-Paul, ©Anaïs Costet

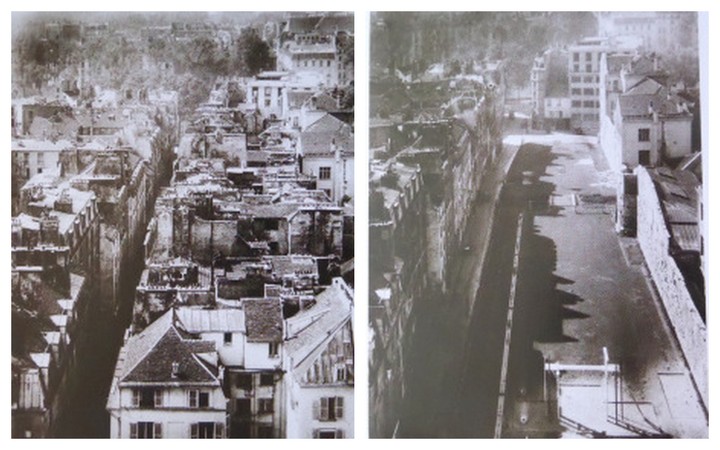

Until the Second World War, this Marais road was built on both sides but in 1946 the decision was taken to demolish the houses on the even side, buildings which originally belonged to the former Ave Maria convent. .

This demolition then allows the medieval wall to reappear. The vacated area becomes a sports field for the Charlemagne high school.

The enclosure has been restored, as it can still be seen today: one hundred and twenty meters long, a wall six to seven meters high (originally rather new) punctuated by two fragmentary towers. gives a first idea of what the XNUMXth century wall was like.

However, it lacks the battlements, the arches for the crossbowmen and the interior walkway. The wall in its foundations is 3 m thick, 2,5 m at its base and approximately 2 m at its top. It is durable and can withstand projectile attacks or undermining work.

Its construction principle is perfectly visible in the basements of the medieval Louvre: between two rows of thick, fitted limestone (interior and exterior facings), the masons poured a solid mixture of rubble and mortar.

The first tower is one of the seventy-seven buildings built along the enclosure; that at the corner of rue Charlemagne, called “ Montgomery Tower ”, is a vestige of the Saint-Paul postern, a “breakthrough” which gave access to the gardens and the eastern suburbs.

The Philippe Auguste compound before and after the demolition of the buildings on rue des Jardins Saint-Paul in 1946

The wall then “crosses” the Charlemagne high school, runs along the west side of the Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis church, up to rue Saint-Honoré. At the intersection was one of the large fortified gates of the enclosure (which today explains the width of the street at this location): the Saint-Antoine gate, also known as the Baudoyer gate.

Then the Philippe-Auguste enclosure goes up rue de Sévigné, to the current fire station. There, it bends towards the northwest.

We find it on rue des Rosiers, an axis which roughly follows the interior path of the wall; we also have a nice testimony to it, at the entrance to the Rosiers-Joseph-Migneret garden: it is another tower, fragmentary, of which we can only see the lower part and which served for a time as a chapel for the nearby Hôtel d'Albret, as the decoration of the walls indicates today.

Remains of the enclosure in the garden of Rosiers-Joseph-Migneret, ©Anaïs Costet

Then the enclosure continues towards rue des Francs-Bourgeois, passing by the school located at 10 rue des Hospitalières-Saint-Gervais (a portion of the wall is visible in the courtyard) then via rue du Marché-des-Blancs - Coats that follow the outline. A new gate, called “Barbette postern” was placed at the intersection of rue Vieille-du-Temple; it gave access to the Temple and Ménilmontant.

Then running under the square (remains exist in the basement) then through the choir of the Blancs-Manteaux church, the wall is again visible inside the Crédit Municipal buildings. In the main courtyard, a marking on the ground allows you to guess its layout.

This marking also leads, at the west end of the building, to another fragmentary tower, discovered during the demolitions/reconstructions of 1880. From the street, we can only see the upper part, rebuilt in bricks and placed on the original stone base.

Remains of one of the towers of the enclosure in the Crédit Municipal, ©Anaïs Costet

The wall then crosses rue des Archives (at the intersection was the “Porte de Chaume” going towards the Temple enclosure), then rue Rambuteau; at numbers 5 and 8, the Parisian road services have also highlighted its route with different paving (a plaque on the wall also reminds us of this).

Beyond, the medieval enclosure takes the Passage Saint-Avoye (private), crosses the Rue du Temple, runs along the “fox wall” (south) of the courtyard of the Museum of Art and History of Judaism, closes the end of Impasse Berthaud to finally arrive at Rue Beaubourg.

From there, it continues its way, beyond the Marais, towards the Portes Saint-Denis and Montmartre before going back down, via the Porte Saint-Honoré, to the Louvre.

The enclosure of Philippe Auguste, ©Paris Historical Atlas

FOR PASSIONATES OFUS

The Enfants Rouges market, everyone loves it

Restaurants, merchants, a photo store, a bookstore... This is how the Red Children's Market presents itself, unique in its kind in the Marais and its capital because it is the only one to offer such a varied and varied range of restaurants. qualitative.

The Marais Jewish quarter in Paris

From the 13th century, the Marais was home to a Jewish community which remained there until its expulsion in the 14th century. Fleeing poverty and persecution, Jews from Eastern countries and those from Alsace settled there in the 19th century. Around rue des rosiers and Place Saint-Paul renamed Pletz…

Victor Hugo, the writer with a thousand talents

Born in 1802, Victor Hugo became a social writer, a playwright, a poet, a novelist and a romantic designer. Nicknamed the man-ocean then the man-century, he is a political figure and a committed intellectual. He found success with Notre-Dame-de-Paris in 1831 and with Les Misérables in 1862.

NOW ON THE MOOD MARSH

Divine brunch at the foot of Notre-Dame

Of course, officially, it is not the Marais. But at Son de la Terre, a barge recently moored at the Montebello quay (5th), the 4th arrondissement is in sight. Moreover, this one is incredible: on one side, it is Notre-Dame flooded with sunlight; on the other, the quays, the book sellers, the walkers, the joggers.

Saka, a cocktail bar like in Tokyo

Here is an address which gives the measure of the transformation of the Marais. And it's enough to silence the grumpy people whose mantra is: “It was better before…” No, everything was not better “before” in the Marais. Besides, there was no American bar like Saka, which cultivates a form of excellence that can only be found in Japan.

Jazz at 38Riv: The highlights of May

The only jazz club in the Marais, 38Riv is the temple of cool and swing. Rue de Rivoli, between Saint-Paul and Hôtel de Ville, its vaulted cellars are the home base of the new jazz scene. Every evening, the magic happens.